The Sound Of Trains

Meeting my late-grandfather through the records he cherished most

“He’d started his life story on a train ride he couldn’t remember.”

- Denis Johnson, Train Dreams

All Aboard

Decades before Ozzy Osbourne became the Prince of Darkness, my grandfather was drunk in a warm living room shouting Alllllll ABOARRRRD while his daughters, tucked into bed upstairs, tried to sleep.

“It was always a late night thing, the cocktails were big-time and he would get those train sounds going at full volume,” my mom tells me over the phone. “It sounded like the house was coming down.”

During the parties her parents would throw in the 1960s, this was my grandfather’s shtick. A devoted train enthusiast, Sturman (or “Sturm” to his friends) would drift toward the turntable with a gin martini and a vinyl record, ready to crank the volume for his unsuspecting guests.

“He’d pretend that you were really there, on the railroad,” my aunt says. “I think it drove Mom crazy.”

At the time, my aunt Robin thought it was bizarre that her father’s record collection was filled with chuggachuggas and choochoos, while her friends’ dads were spinning Dean Martin and Louis Armstrong.

Now, five years older than her father ever was, Robin finds herself searching YouTube for train sounds late at night. Videos that loop for hours so she can relax and finally get some sleep.

Introductions

I’ve never met my grandfather. He died in 1991, three years before I was born.

But I do remember wearing his pin-striped train cap around our house as a kid. The rigid canvas scratched my scalp, and a long floppy brim blocked my eye line as I slid down our basement stairs in clean white socks.

I remember the stark black-and-white-ness of that hat; I thought it looked punk-rock, loosely resembling the bleak color palette of posters pinned up to my bedroom wall — Green Day, Avril Lavigne, pages ripped from TransWorld skate mags.

Sturm wouldn’t know any of these references. However, he was up there, too, or at least his art was.

Even though they weren’t my style, two train cars he’d painted hung above my childhood bed for years. I think my mom wanted to introduce him to me somehow, sneaking in a sign that her father and I were linked despite the circumstances.

“He would have loved you,” she used to say. “He always treated me like the boy he never had.”

Now, living in an apartment in a different city, Sturm’s paintings are back up above my bed. Two idyllic midday landscapes marked by alternate versions of his signature, as if at the time of painting, he was still trying to hash out his identity.

Sharing the wall is another one of his.

A photograph we uncovered after my grandma died in 2020. A blown out black-and-white image of an unidentified hulking soot-coated steam engine beaming its headlight through a dark foggy night.

For the past five years, I’ve imagined my grandfather taking this photo. Standing on the wet cement platform, alone, the cool metal of his camera pressed to his cheek, the mechanized heartbeat of the resting metal beast humming through the soles of his shoes.

Legacy

Almost everything I grew up learning about my grandfather was shrouded in a similar darkness. His legacy was spotted by unfortunate facts passed down by the people who loved him most.

Failing the physical for the WWII draft; dreams of becoming an artist squandered by a life in corporate sales; money problems; driving around with a trunk full of empty gin bottles; jaundice and liver failure; and the unfiltered Camel cigarettes — four packs a day for 40 years — that eventually killed him at 65.

My grandmother, Lydia, who I could talk to about anything, was an expert at avoiding questions regarding her late husband. I never pushed it.

But all these years later, Sturm’s love of trains — by far the most enthusiastic sign of his existence — has expanded into something more.

Oddly enough, it began when I mentioned SNL-graduate Fred Armisen’s new record, 100 Sound Effects — a quirky nod to the rich history of broadcast sound-making — to my dad.

“You know your grandfather used to play train sounds on vinyl, right?”

The question prompted me to call my aunt and my mom. They’re not sure what specific records he had. Perhaps Rail Dynamics (1952), or Whistling Thru Dixie (1961), Steam On The Horseshoe Curve (1961), or even Interurban Memories (1961).

But the idea that he collected them and played them leads me to believe Sturm might have been happier as a train conductor than a salesman.

In The Field

These kinds of records were meant to immerse the listener not only in the sonic atmosphere of a rail yard or train car, but in an actual historic moment. While sound effects vinyls were born from 1930s radio via superficial sound design — like shooting blanks off by a microphone to signify a murder during a live story broadcast — others were true field recordings.

Each track on the Interurban Memories album, for example, contains sounds from an actual train trip, whether it’s January 4th, 1959, riding along California’s “Whistle Alley” with the “wild harmonics” of blimps flying up above; or the sound of “wigwag bells” and “auto horns” from a classic 1920s train car cruising down Hollywood Boulevard on November 1st, 1959 at 1:15PM.

Instead of creating fictional worlds, these records showcased the real world at a precise time. These moments would forever be lost without someone’s effort to preserve them on wax.

Daily Entries

This idea, that you could play back the sounds of an everyday moment on vinyl eventually pushed me to research my grandfather’s life by immersing myself in another kind of record.

Three of Sturm’s journals have been sitting on my shelf for years, but I’d never felt the need to go through them until now.

I started in 1976. When Robin was at Russell Sage College in Troy, NY and my mom was a senior in high school, driving around town in the family’s broken-down Ford LTD. I can picture the house from being there as a kid, but I’m forced to reassess it in a different era, through another man’s perspective: Returning from the office at noon for lunch, then again around 5:15pm for cocktails and supper, grateful to be in the warmth of his home with his family, already dreading the next day of work.

On the page, Sturm cried when the family cat, Archie, died. He called his sister’s husband Glenn for $1,000 so he could keep his daughter Robin in school. He drove down to the local train station for updated Amtrak timetables before a big trip.

Train Dreams

Reading my grandfather’s journals reminded me of Denis Johnson’s Train Dreams, a mesmerizing novella documenting the lonesome, tragic and curious life of a day laborer named Robert Grainier in the depths of early 20th century Idaho.

After a disturbing scene in which a gang of railroad workers attacks a Chinese immigrant on the Idaho panhandle, the book follows Grainier’s trip through time. Eventually, what’s real becomes blurred by what haunts him, with forgotten memories sparking up from the fire of his uncertain past.

“Now he slept soundly through the nights, and often he dreamed of trains, and often of one particular train: He was on it; he could smell the coal smoke; a world went by.

And then he was standing in that world as the sound of the train died away. A frail familiarity in these scenes hinted to him that they came from his childhood. Sometimes he woke to hear the Spokane International fading up the valley and realized he’d been hearing the locomotive as he dreamed.”

In the story, trains resemble Westward expansion and the settling of “Frontier America,” but more so, they embody the steady, unstoppable motion of time.

Following Grainier’s observations, his molasses grit and undying routine, felt like following my grandpa through the yellowing pages of his black leather-bound journals.

Daily entries give way to an atmosphere made up of palpable repetition: Breakfast, drive to work, drive home for lunch, drive back to work, drive home for cocktails, supper, Johnny Carson, writing, sleep. The image of a grown man in another time reflecting on his day-to-day grind. “What a day—Shit!”

Like Grainier, I think Sturman aimed to keep his labor and his identity separate. He cherished being home, describing every meal as delicious — “most delightful steak dinner”; “(Spaghetti extremely good)” — and naming the love he had for his family, as well as his sadness when they were gone — “I’m really going to miss Wendy this weekend.”

And like Grainier, who blamed himself for not saving his family from a forest fire, Sturm plainly states his blunders, his exhaustion, his fears, his leisure, his inability to manifest solutions to some of life’s worst challenges.

Through that daily exercise, though, his voice — a voice I’ve never actually heard — begins to shine.

No one in my family had ever mentioned Sturm’s urge to write everything down. This act alone presents a fresh lens through which to view him and his decision to record personal, mundane events.

Related

Well-recorded mundanity is what I’ve always strived for in my own journal.

For the past 10 years I’ve been recording what I see every day, as well. Without any knowledge that maybe Sturm passed this urge along.

I do wonder if our urge is the same. My entries have no real page limits like his, and I get into my feelings, insufferably at times — he did not. But I’d guess our urge to record the day is more about a means to slow the unstoppable motion of life for just long enough to feel grateful and move on. To be able to start the next day without the last one weighing us down. I guess one might call it a coping mechanism.

In Your Image

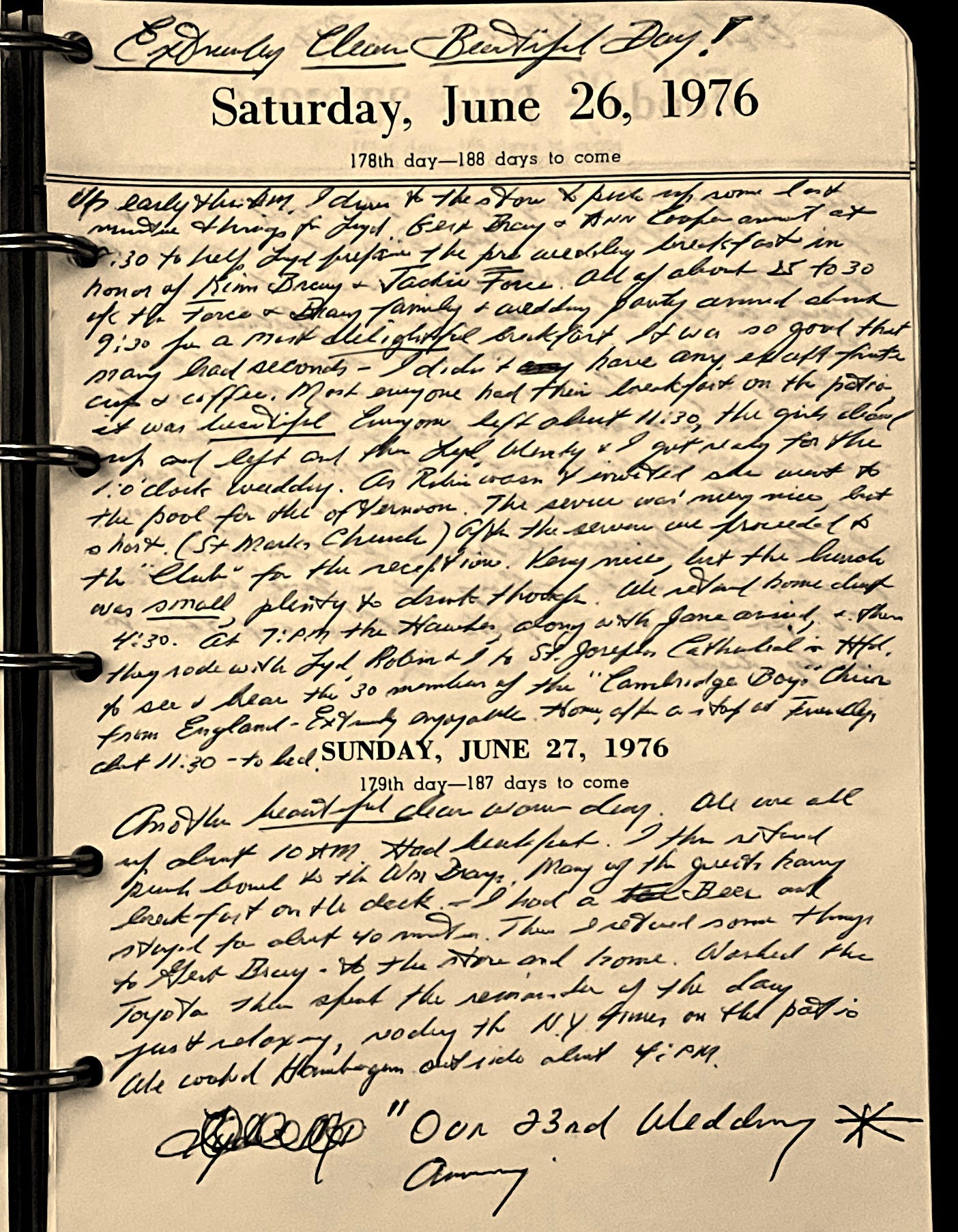

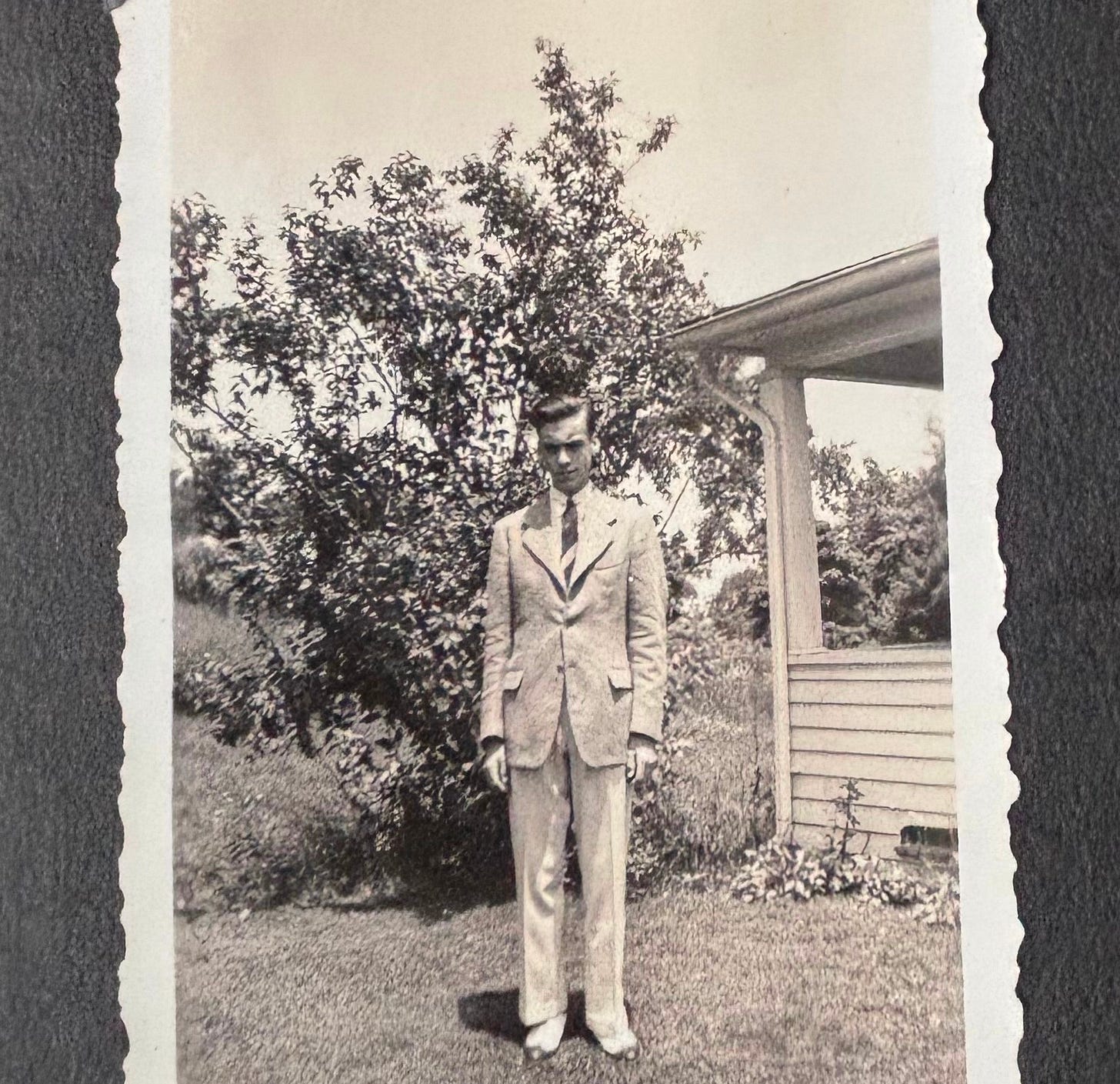

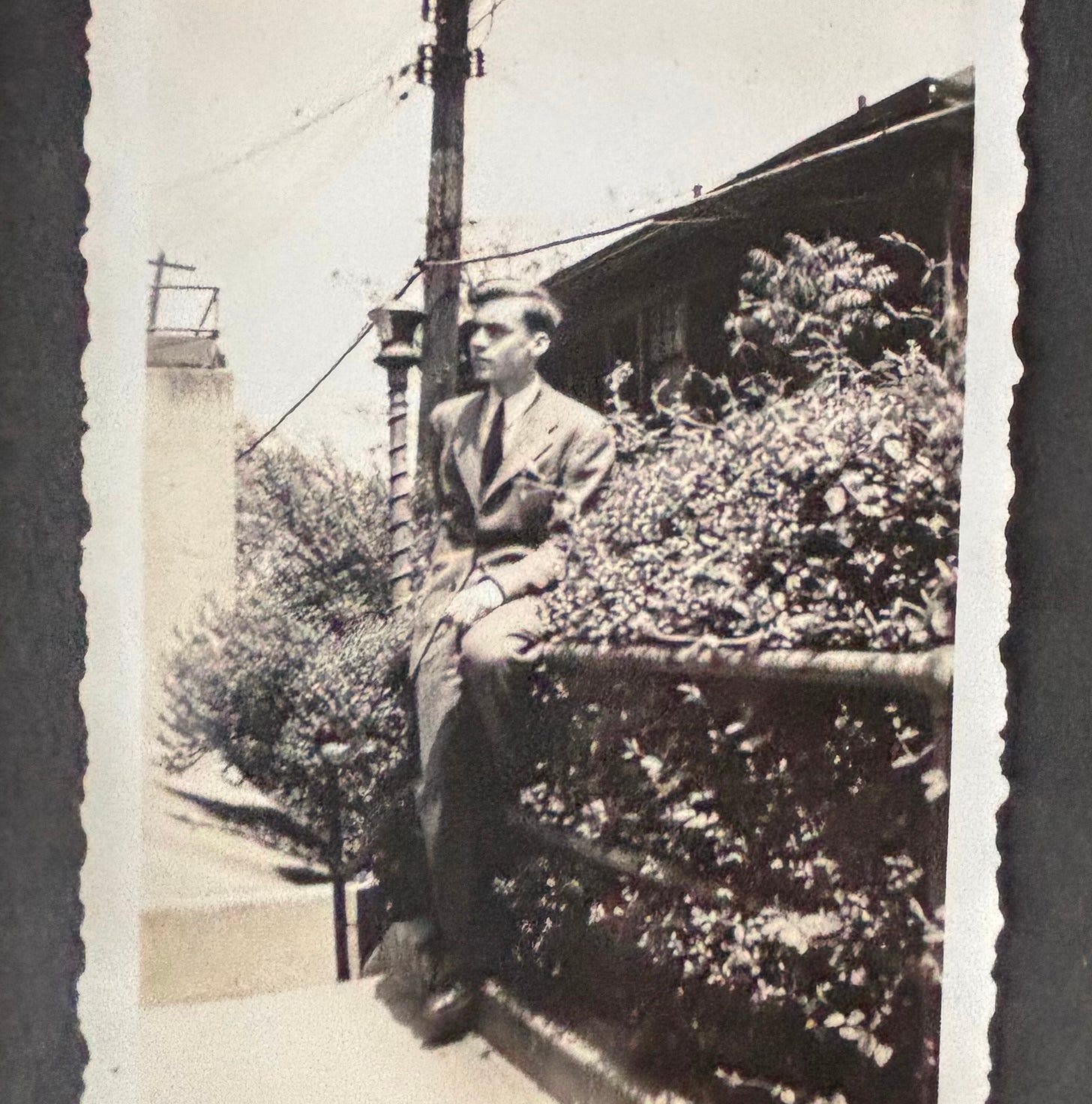

Another reason I was inclined to finally pick up Sturm’s journals was because of the photos my mom’s been sending me. See for yourself:

Her father as a boy in 1938.

Posing in 1942 on the day of his junior high graduation.

Or posing that same year, in a bush.

Or a few years later in the local newspaper, alongside fellow actor Barbara E. Morris for the high school play.

Or with my mom and Lydia (looking totally fed up) while holding Archie the cat and a cigarette.

Or Sturm and Lydia posing in middle age (and color) — my grandmother in a pink checkered dress, Sturm in a navy blazer, his thick eyebrows raised an inch from his smiling face, his sister’s painting of a waterfall above the model train set lined up on the fireplace mantel.

That painting also lives in my room now, resting on two little nails, unframed.

My favorite photo though is of my grandfather lying back on the beach, in pressed slacks, his shirt off, shades on, smiling, propping a to-go martini against his bare stomach.

When I showed my friends this photo they said they saw me in it. Which made me buzz, because I saw myself in it too. The same hairline, sure, but also a personal essence, a part of who I am.

That said, I’m plagued by a fear of following Sturm’s path. I have been since I was young. Failing to realize I’ve forfeited my essence before it’s too late, shadowed by shame, drinking too much, drowning.

But now I can see that his is a cautionary tale written in full. A warning, a screeching train whistle. And for that I’m thankful.

An End

So far, my favorite line in his journals ends an entry on Wednesday, January 21st, 1976:

“Had a drink and then a delightful ‘Roast Lamb’ dinner. The snow coming down hard as I write.”

It’s the only time I’m truly able to picture him alone, writing.

I wish I had found some of Sturm’s old railroad records in my grandmother’s attic. I would have played them at parties, too, in Ridgewood, Queens. Shouting Alllll ABOOARDDD to an unsuspecting crowd and the twenty-somethings who live downstairs.

Instead, I break out the records passed down from my aunt and mom, stuff from when they were still teens — Saturday Night Fever, Earth Wind & Fire (probably more party-appropriate).

I’m sure Sturm heard these albums through the floorboards, too, booming from his daughters’ shared bedroom while he sat on the living room couch, by the fireplace or picture window, legs crossed, sipping a drink, fanning through the Hartford Courant, listening and knowing he’ll write it all down later.

I can see it so clearly.