A Jigsaw Falling Into Place

An essay on Radiohead, uncertainty, and the phenomenon of losing someone you've already forgotten.

Note: Before you begin reading, I just want to say I’ve been struggling through this bad boy for over five years. Every time I give up on it, though, the funniest thing happens: I have a dream about my old friend. As if he’s trying to remind me to come back and sort it out once and for all. Or maybe it’s just my egotistical psyche. Either way, sharing this makes my skin crawl. But heres a finished draft anyway: an ode to memory, music, adolescence, and the irrepressible power of friendship. Enjoy!

You’re alone on the edge of the pool, where the shallow and deep ends meet. It’s golden hour. I watch you dive in. Plaid boxer shorts billow out from the waistband of your swim trunks. We don’t say much to each other. We just swim around until the pool closes, careless and curious, like nine year olds are. From then on, I begin cutting the netting out of my swimsuits so I can wear boxers too.

Twelve years later, my mom presses the home phone to her chest. Her eyes are wide. I’m in the courtyard of her new home, crunching on a piece of toast, home for spring break. The winter’s white-grey sheath has begun to glow green. Dozens of mirror-like droplets dot the plants in her garden. That’s where I’m looking when she tells me you died.

Even though you and I haven’t seen each other since high school, I think my mom’s worried that your death will break me — the proverbial straw. Over the past month, my girlfriend and I broke up, I was fired from my bartending job, and, soon, I’ll be graduating college with no job prospects. I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t anxious. Anxious and hungover.

But I continue to fixate on the flowers in the garden. Pinks and yellows lit like fire against the wet stone walls. Silent, I walk down into the grass, noticing how each green blade moves against the arches of my bare feet. I feel high, tuned in. It isn’t joy, but it feels oddly good. I’m present, a bud about to burst.

The sensation disturbs me.

A heap of band Ts and khaki pants, plastic nerf guns with orange foam ammunition, a bulky helmet for your dirt bike (that I never saw you ride), checkered button-downs, several mismatched sneakers, a large white cage for your guinea pig Foo, wooden drumsticks, a bunk bed with full-sized mattresses, two windows and a giant stack of CDs. This is your bedroom in fourth grade.

My eyes bulge, I can’t see the floorboards. It doesn’t match the rest of your parents’ house, which is tidy and bright, like a seaside cottage.

“We gotta clean this,” I say, standing still in the doorway. I surprise myself. My mom is always on me for not cleaning my room, but this isn’t a few misplaced shirts, it’s full-on disorder.

And, for whatever reason, you agree.

For two hours we hover over your personal belongings, sorting side-by-side. What do we talk about? Maybe the fact that you have a television in your room (so cool!). Also the season of South Park you own on DVD, which I pretend I’m allowed to watch. I’m sure Blink-182 comes up, too, since it’s the CD that catches my eye: The Mark, Tom, and Travis Show. A drive-in movie themed cover with cartoon versions of each band member, complete with tattoos, piercings and a blonde babe with a signature Sharpied across her boobs.

As you slide open your closet door, I hold the CD case up to the light like a crisp one-hundred-dollar-bill and admire the “Parental Advisory Explicit Content” sticker stuck to the bottom left corner.

“This is unedited?” I ask.

“Yeah, it’s pretty crazy,” you say, smiling. “They say ‘fuck’ a lot.” We both crack up. Then you snatch the CD from my hands. “You gotta hear this.”

The top of your boombox springs open and you place the disc inside. It’s a lavender color with the three band members’ chuckling cartoon heads displayed on top. Skip to Track 8. Airy cries from the crowd, a redundant guitar strum and Tom DeLong’s whiny vocals: It would be nice to have a blow job / It would be nice to have a blow job…

On and on as I sit on your bottom bunk, folding shirts, giddy with excitement. I’ve never heard anything like it.

The song ends and I can’t help but ask. “So…what exactly is a blow job?”

“I think it’s like when a girl...blows on your, well, you know.”

You point to your crotch and it’s clear that you’re not entirely sure, either.

“Like when something’s too hot?”

“Ya, probably.”

I nod and turn my attention to the last heap of clothes, where I find an item even more valuable. An airsoft gun. I’ve never held one before. It feels so real, a pistol, heavy, all black with a pointed orange tip, the only clue that this is a toy. I think you can tell I’m obsessed with it.

“We can go shoot it if you want,” you say, shrugging.

I look around the room: the clothes are folded and placed in drawers, the CDs all have their appropriate sleeves, the beds are made and the floor is visible.

“Sure,” I say, nodding, as casually as I can. “Sounds good to me.”

You grab a plastic jar filled with tiny neon-green balls and slip something else into your pocket. Before I can ask you what it is, we’re rushing downstairs and out the front door.

Like my neighborhood, about a mile away, your street backs up to a wooded area with a pond and a few walking trails. Suburban-woodsy. A ring of post-colonial houses and streets coated in pine needles. Safe spaces for children to get into trouble.

Facing the pond, you pull the pistol from your waistband and cock back the top. It makes a satisfying clicking noise and looks similar to what I’ve seen on Law & Order reruns after school. When you pull the trigger there’s a reverberating Ping! and a neon fleck flies out into the water. I can’t wait to get my hands on the gun. You shoot it again, this time at a squirrel running along the branch of a tree. The animal scampers away unscathed and we’re both relieved.

You hand me the pistol and I cock it like Axel Foley in Beverly Hills Cop, ducking behind a small bush as if it were a burned out car being fired on by assassins. Distracted, I don’t see you pull the firecracker out of your pocket, light it, wind up and chuck it in the air. It goes off above my head with an impossibly loud bang and we both scream then sprint back to your house. We hide in the darkness of your garage, like wanted felons.

Years after you die, Radiohead’s “Jigsaw Falling Into Place” plays through my headphones as I drift off in bed and dream about your funeral.

Everything’s preserved. The church we used to attend. The grassy hill. The red stone wall along the main street. The outdated gymnasium with yellow floors and brown trim. And the hulking youth group bus that would break down on long rides, puffing smoke into our eyes through overhead AC units. Even the ushers look the same, standing at the double doors our families walked through every Sunday for the late service. Our fathers look crisp in pressed ties, cheeks bright pink from a close shave. The steps where we were confirmed are covered in the same ugly green carpeting.

I’m looking at everything from above, pressed to the ceiling, tucked up behind the slow-spinning ceiling fans. There’s an open casket sitting on stage with your body wrapped tightly in its womb. I watch our youth minister, our friends and families, as they rapidly age.

Your mom, with greying hair, collapses on stage like a pierced gladiator, buckling and slashing underneath the overflowing congregation. I fall from my perch and wake up sweating, surprised you’re still on my mind.

In sixth grade, you sit down at the lunch table wearing a baggy black hoodie dotted in small circular pins, all red, black and grey. When I comment on how cool I think it is, you seem almost embarrassed, unsure of how the sweatshirt suits you.

“I saw Green Day last night,” you say, quietly. Maybe you know I’ll be jealous. I am, of course, but I also know that to see Green Day, my favorite band, is so far outside the realm of possibility that I barely let my envy register.

At 12 years old, my parents would never consider letting me go to a real concert, not for a band whose newest CD features a bleeding heart grenade on the cover.

Spiked hair, studs, thrashing guitar, and angsty anti-authority lyrics has been my M.O. ever since Good Charlotte came out with their career defining album, The Young and The Hopeless in 2002. But while I want so badly to imitate these tattooed pop-punk pioneers, I’m well aware that I can’t actually look like them. I’m not allowed.

The closest I get to self expression is a T-shirt my great aunt from Canada sends me of a skateboarding monkey sliding down a rail on his crotch with the phrase, “Don’t Forget Your Cup” written out across the chest. The other shirt she sends me — of Harry Potter smoking a skinny joint (“Harry Potter and the Sorcerer is Stoned”) — is kept captive somewhere in my parents’ closet.

The year I turn 30, I dream about you for the fifth or sixth time.

We’re in a dark room with red and blue spotlights hitting a small stage-slash-bandshell; the nightclub somehow resembles where we graduated high school.

The place is packed. You’re playing your own funeral, sitting on a chair and strumming a guitar, looping yourself with a pedalboard at your feet. I stand in the back trying to focus on the music but I can’t hear you well enough. I can’t feel your presence as much as I want to. You just sit there, hunched over the guitar, plucking chords until a soundscape emerges and engulfs you, all red and blue. You don’t speak between songs. You take on a holographic state.

When the concert is over you evaporate. I fling open the door to the street. It’s sunny and bright. We’re on a sidewalk, the two of us, talking but not really saying anything; you’re speaking a language I’ve never heard before. Your mom pulls up in her blue Dodge Durango, the same car she had when we were kids, and you climb in.

Before I wake up, I’m standing in the street watching the car drive away.

The bitter, minty smell of Listerine is pungent as we wriggle out of our shorts, revealing boxers spotted in hockey sticks or baseball mitts or little beagles playing cards.

There are glass spheres standing between each sink. They’re filled with black plastic combs wading in pints of Barbicide. When I was younger, I cupped the blue liquid into my blonde hair as if it were dye (an earnest attempt at appearing like my punk-rock idols) but it ran into my eyes and made me scream. My mom had to rush me home and wash my eyes out in the bathtub, fearing I’d go blind.

But now we are 13 and know better.

We know which peoples’ lockers are open, which ones have books of matches we can use to light stuff on fire in the woods, and, more importantly, which ones have the big bottles of Head & Shoulders hidden inside — a thicker, smoother alternative to the pink body wash loaded into the hanging shower dispensers.

The shower stalls don’t have doors but you don’t care. You ditch your boxers and plop down on the tile floor. Water runs down your legs toward the communal drain. You don’t warm up. You just start jerking off, no mercy.

“Here!” you say, sliding the bottle of shampoo across the slick turquoise floor. I snatch it up and face the wall, squeezing a healthy amount of gel into my right hand.

I’m embarrassed by your showmanship. I choose to stand under the shower head and slip my hand below my wet shorts, working in private. But I’m also desperately curious. I hear myself yell, “Is it working?” over the sound of running water. You let out a howl and I can’t help but spin around to see that grin of yours, you are beaming. I guess what they said in health class was true.

“Are you awake? Colin, wake up.”

My eyes force open. Sitting on the edge of my twin bed is my mom. She wears the same stone-cold expression as a TV detective interrogating a disgruntled suspect. I’m disoriented, having already fallen asleep. I cringe and turn slowly to my alarm clock. It glows red—2:22 AM.

“Colin, look at me.” My mom shakes my shoulder. “What is wrong with you?”

“Whaddya mean…?” My voice is a low rasp.

A pair of chunky Skullcandy headphones press tightly against my neck. I struggle to remove them, but eventually pry them loose and toss them to the floor. The lime-green cord descends like an escape ladder at a house fire.

“What do you mean?” I choke. “I’m fine.”

“You are not fine.” She glares down at her 14-year-old son, her spidey senses tingling. Although my mom pursued a career in interior design, she majored in criminal science at college and always dreamed of being a private eye. Tonight, I learn that she’s equipped for either profession.

“The second we got in the door, you threw open the cupboard and grabbed a box of Cheez-Its and a box of Pop Tarts and ran down to the basement. What was that?”

“I was just hungry,” I say, my eyes mere slivers. The headphones, which are still connected to my iPod, broadcast the ghostly din of Thom Yorke’s vocals from somewhere on my floor: Just as you dance, dance, dance…

“Colin, I’m serious. I smelled something in the car when I picked you guys up tonight. Don’t lie to me.”

She keeps questioning and I keep denying until there’s a long uncomfortable pause. A breaking point. I know I’ve got to give her something.

“Okay okay,” I say, inching my body upright against the wall behind me. “We may have smoked a littttle weed.” The words feel impossible in my mouth, like chewing glass. I can’t believe it’s come to this. “I’m sorry.”

“Colin,” she says, staring me down. “It smelled like booze.”

Fuck.

The next day, after school, you and I change into shorts and lace up our muddy sneakers in the parking lot, preparing for a few hours of hell: cross country practice — a team we’ll both be kicked off of senior year due to our tendency to skip races and smoke joints in the woods. Gravel crunches beneath our feet as we fall back behind the pack of skinny boys. I fill you in on my confession.

“Dude, you’re such an idiot! Why did you say that?!”

“She caught me off guard, man, what was I supposed to do? You’re lucky I convinced her not to call your mom.”

You shrug, panting. “I guess that’s true. I can’t even imagine what my mom would have said, not that it would have mattered.” For a moment, we run down the mile-long path in silence. “Hey, we had a good time, though. Amanda was so fucking cool, I think I’m gonna ask her out.”

“Well have fun at homecoming, cuz there’s no way my parents are going to let me go.”

“Ha! Sucks, bro. But at least both your eyebrows are still there.”

“Shut up. That pipe of yours is dangerous, dude. I thought I singed my face off when I took a hit.”

“Wait,” you say, suddenly serious. “Do you think your mom hates me?”

I laugh at how much you suddenly care.

“No. But you’re definitely not her favorite right now.”

You slow down. You look crushed.

Sophomore year of college.

I’m in the library past midnight deleting the same paragraph over and over, trying to write a short story for my intro to fiction class. About to give up and return to my cramped dorm room, I remember something: the deal you cooked up with one of the lifeguards at the country club pool. Your mom’s oxycodone for weed.

As I begin to type, I remember that lifeguard. He was in his early twenties and spoke like he didn’t give a fuck. Sure. Whatever. His chest was shaved, his swollen muscles a fitting canvas for the two rottweilers with bloodied fangs tattooed on his back, like Edward Norton in American History X. He was eventually fired for a DUI, his second in the span of a year.

The dog tats freaked me out, but I could tell you were impressed. You saw something in the lifeguard that mattered to you.

Perhaps the day you and he made your first trade, in the back of the men’s bathroom, where as kids we’d spent time before swim meets, swapping swim trunks for jammers, was also the day I could feel something begin to split.

I watched you follow the dog fangs into the bathroom and reemerge smelling of skunk, the older guard still shirtless, donning thick black shades and a whistle, which he twirled around his finger as he traipsed down the gauzy steps to the white plastic chair hanging high over the deep end.

“He crushed up the pills and snorted them right off the counter,” you said, in awe. I felt like I was trapped in a real-life D.A.R.E module. Not only were you pedaling opioids, but you had stolen them from your mom’s medicine cabinet.

As a kid, there are great forces at work. The inability to travel freely. A lack of funds. The deep-seated fear of disappointment. And parental guidance, in whatever form it takes. But as teenagers, the firewalls to adulthood begin to melt away.

In the story I am writing, the protagonist is part jacked lifeguard, part you, and part me. On a sunny day when the pool is packed with people, he climbs the slick ladder to the high-dive, walks to the end of the board and jumps, launching himself into a perfect swan dive. While airborne, the drugs hit, and there he goes, down into the depths of his trip.

Later that semester, my story is published in the college literary journal. At the journal release party I stand behind a boxy podium and read my words for a small crowd of professors and English majors. I don’t expect anyone to laugh; this is serious stuff. But people are in hysterics. I force myself to laugh along, happy to entertain. Happy to separate myself from the reality of that sketchy lifeguard, the alarms in my head, and you on that off-kilter day.

Not long after that strange day at the pool, I feel compelled to confide in an adult. So, like a dweeb, one day after school I go to see our youth minister, The Rev. We meet at a crowded coffee shop down the street from the church.

A year out from smoking weed for the first time (with you), I probably think the stuff’s more deviant than I should. But I’m staring down the barrel of a new era. High school starts in the fall and I’m doing what I can to convince myself that you and I won’t start to drift once the summer ends.

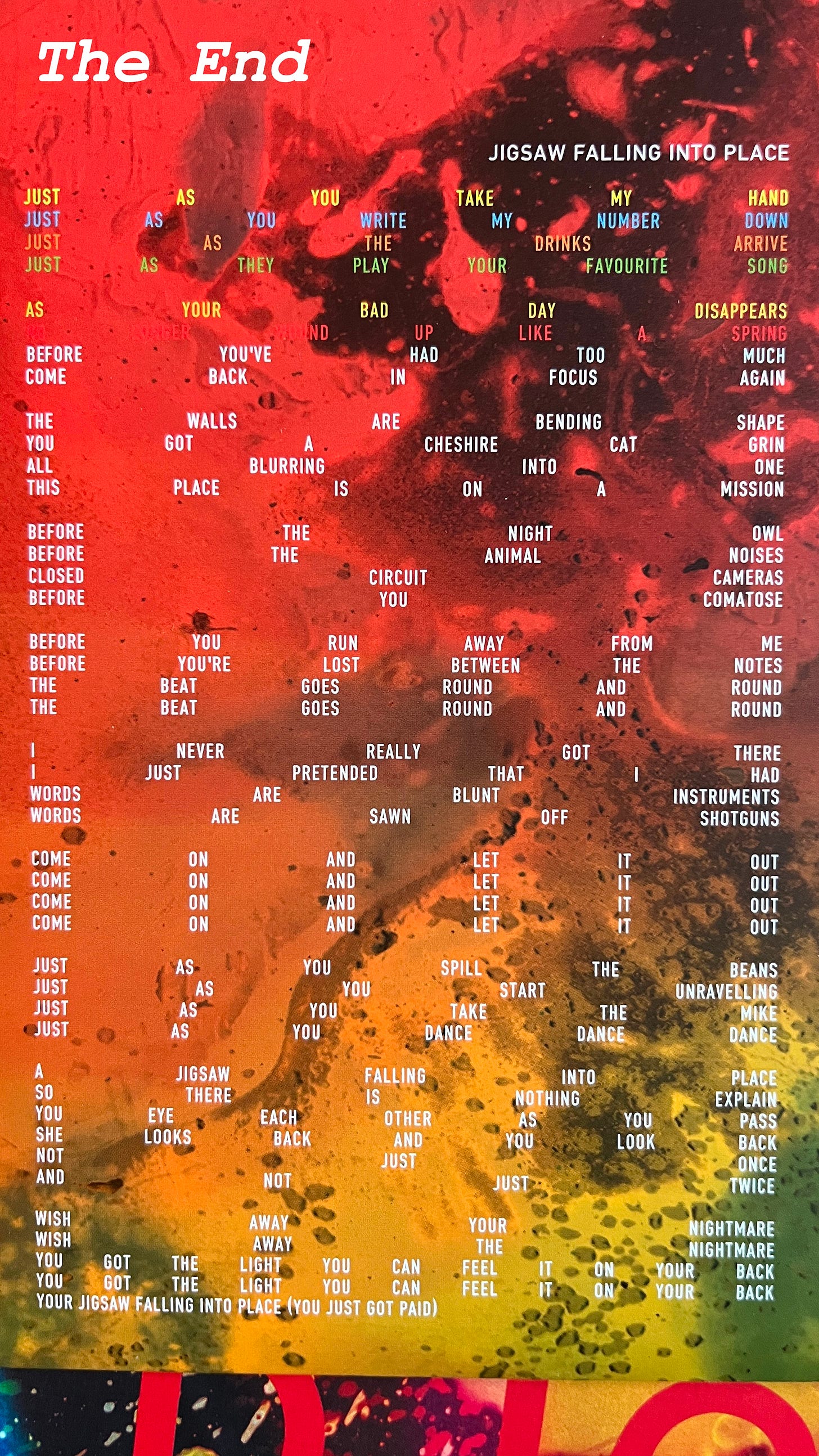

As The Rev tries to offer some advice, I try and listen. But there’s a song playing over the coffeehouse speakers with an eerie acoustic guitar strum. The vocals are haunting and the drums are metronomic, with quick, perfectly timed fills. I’m mesmerized. I pull my phone out under the table and open Shazam.

Later that day, I check the app and see “Jigsaw Falling Into Place,” by Radiohead. I listen to the song on repeat in my room.

After I graduate college, over a year since you’d passed, I come back to visit my mom and set up another meeting with The Rev. I haven’t attended church since high school and I no longer identify as a religious person, but it’s comforting to reconnect with someone who not only knew you but also led your funeral service.

From behind his cluttered desk The Rev, now with graying hair, shakes his head and says, “I keep thinking back to that chat we had when you guys were in middle school; it didn’t seem like a huge deal at the time, just a little weed and whatnot—adolescent experimentation. But I might have been wrong.”

I don’t know what to say. Aside from a couple of rumors I’d heard about a laced drug you’d bought online, there’s nothing definitive in your obit; I still don’t know exactly how you died.

I’m rummaging through the albums in my apartment, looking for something to play while lounging on the couch. In a pile on the floor, I stumble upon my roommate’s copy of In Rainbows and start with the B-side, placing the needle down gently in the groove of the fourth track: “Jigsaw Falling Into Place.”

It still sounds as good as it did during my meeting with The Rev. It sounds as ominous as it did during my mom’s interrogation, and as elucidating as it did in my bed as I drifted off into an imagining of your funeral, which, in real life, I never attended.

I slide out the liner notes and read the lyrics as the song plays out.

Just as they play your favourite song

As your bad day disappears

No longer wound up like a spring

Before you’ve had too much

Come back in focus again…

Before you comatose

Before you run away from me

Before you’re lost between the notes.

You got the light you can feel it on your back

Your jigsaw falling into place

Thinking of you, the words almost seem too on the nose. I wonder if you ever heard this song when you were alive. Did you even like Radiohead?

Moments after I finish reading my story in college, and step down from the podium, I decide to bury you forever, whether I know it or not. In fiction.

But, as it goes, when you die, I’m forced to dig you up.

That’s why I’m dialed in, blissing out in my mom’s yard. For the first time in months, I’m not stuck obsessing about my future as an unemployed English major, or contemplating my probable OCD, or running through endless versions of who I might become in “the real world.” For a drawn-out moment, I forget my own debilitating fictions and dive back into the past, with you:

I remember the first burn of liquor down the back of my throat. Raspberry Smirnoff. You pull the bottle casually from the back of the snack kart, a four-wheeled off-white machine stocked with booze, and I’m surprised to see it parked out here on the 7th tee, unmanned, its small black tires resting on a carpet of brilliant green.

And each row of bottles is stuck with silver pour spouts, shimmering pink and orange under a creamsicle sky.

“Let’s just take one swig each,” you say, using the tips of your fingers to pry off the spout.

And after a few seconds, there’s a pop as the spout’s black rubber base squeezes out of the bottle and falls to the ground. You raise the circle of glass to your lips and tilt the comically large vessel toward a row of swaying pines, their dark tips just blocking the setting sun.

And as the clear liquid hits your tongue, your eyes become slivers, your whole face a scrunched mess, like the cartoon guy on Warheads wrappers. But sucking sour candy looks different; this new act involves swallowing air through your teeth, like something’s burning or you just stubbed your toe. Eventually, you hand me the bottle, mustering enough of a breath to smile. “Not bad,” you choke.

And I’m at Camp Jewell with our fifth grade class, playing bystander to your first kiss. You and Meg on the rounded dock at dusk. I’m descending the wooden steps as another couple guides you two toward the water. The hierarchy has never been clearer; these preteen ushers have been dating longer and are to be trusted as experts. The excitement on your grinning face is tangible. I want it for myself. We want the same things.

And, it’s two years later, I’m listening to Brittany describe your “real” first kiss, which went down in the stairwell of a University of Tennessee dorm. She laughs and says you were awkward, that you bear-hugged her. The next day, I’ll wrap my arms around Kate in the middle of the massive university pool, noticing the goosebumps on her bare skin as you make us blush with ceaseless commentary — Dang, look at you two!

And it’s there, in Tennessee, on a summer church trip, in the sticky southern heat, where I witness someone so comfortable in their own skin. Each afternoon, you walk around our shared room butt-naked, eating Peach-O’s from the plastic bag, yammering on about Brittany and whether she actually likes you or not.

Because of this, we are late to every “God-Is-Great” activity. All week, we pace back and forth in front of elevator doors, arguing whether or not bashing the down arrow will make a steel box plummet faster.

The news of your death travels fast. My phone erupts with texts and voicemails from people we knew when we were kids. I’m not sure how to tell them about us. How time poured between us like wet cement. The thought makes me dizzy. Days later, I flake out on your funeral and head back to school.

It’s becoming clear to me now that your death gradually shifted the way I think about memory. Nowadays, I see the act of remembering as a natural resource. Like focusing on the breath during a panic attack. For me, in moments of severe change, you remain a beacon, something I can grasp for.

It’s simple, really; remembering you helps me remember myself.

It’s one year after your funeral when I decide I need to see your parents.

Your mom’s hair is just as straight and white-blonde as it always was. Your dad is just as comforting and kind.

Inside your house, I give them both big hugs and they lead me into the renovated kitchen. The new island is huge—white marble. It looks different and I’m relieved. We sit on three wooden stools and your dad hands me a Corona with a lime wedged in the top. I think about the bottles of cheap liquor you and I used to sneak into the basement and smile.

“He was so close to graduating,” your mom says, flipping through a photo album someone made of you. The pages are brightly colored. She’s grinning, your mom, looking down at a picture of you posing on a sand dune, a wall of spiky grasses behind you. “He was majoring in Environmental Science.”

“That’s so cool,” I say, jarred by how little I know about your final years. I’d heard you transferred schools at some point but I couldn’t say where. Regardless, it feels good to see your face again. Your slanted smile framed by plump dimples, your squinty eyes and that wave of shaggy brown hair. In later pictures, a thin hemp necklace with a singular bead hugs your skin.

As we chat about the past, I can’t shake what The Rev mentioned earlier in our meeting. That you were home for spring break as well and passed away upstairs. That your mom found you cold in your childhood bed.

You had a bad heart, she tells me now. I don’t ask her to elaborate. Instead, I think about your American Idiot hoodie for the first time since sixth grade. Specifically that heart-shaped grenade and the firecracker you once launched into the air above my head.

After I say goodbye, I decide to drive the long way around your block, spotting a bench in the same place we once fired that pistol years ago. It’s rooted on the edge of the pond, overlooking an island of water lilies. The metal bench reflects the afternoon sunlight in sharp unmoving bursts. I stop the car and get out. There’s an inscription dedicated to you, it’s carved into a sign hanging on a tree branch: “Buddy’s Bench. To all of those who find joy in nature.”

Days before we start high school, my family invites you to stay with us at a rental cottage on the Connecticut shore. The cottage is over a century old, a house of wooden beams, creaking floors, and countless ghost stories. You arrive at night.

As your mom backs out of the driveway, I motion for you to drop your bag and follow me down the hall.

In the screen porch on the back of the house I unhinge a painted clasp between two warped windows and push them open. A cool breeze hits our faces as smells of salt and beachgrass seize the room.

You look out. It’s all water, but you don’t see it yet. An endless black ocean. Your eyes are still adjusting. A glowing strip of foam rises and falls, a small wave breaks on the shore, and I watch the whites of your eyes expand. In a soft voice, you say, “Woah.”

I’m in my thirties now and I’m still dreaming of you. It happened again the other night.

This time, we’re at a community college in Santa Monica. It’s my first time in California. As I pass the campus on the way to the beach, I notice someone in a Quicksilver hoodie walking between classes. It looks just like you. I know you’ve been dead for a decade, but I spend the rest of my vacation following the student around. Tracking him like a private eye.

My suspicions are correct! It’s you. You’ve been out here this whole time. Alive.

Feeling deceived, I confront you. You explain that you had no other choice. A life-changing opportunity arose, your mom sent you to California and covered everything up back home after you left town. This was for the best.

You’re an adult now, but your eyes contain the same spirit of your old kid self. I believe you.

Boarding my flight back to New York I feel a genuine comfort in knowing that I can come back and see you whenever I want.

When I wake up, I know that much is true.

This really nails how grief doesnt follow a timeline and how someone can dissapear from your daily life but still show up in your subconscious for years. The way the Radiohead track became this unintentional thread connecting all these diffrent moments is kinda haunting. Had a similar thing happen with a Tom Waits song after losing a mentor, still cant hear it without feeling transported.